There is one important type of problems in which we know the derivative of a function (its rate of change, the slope of its graph) and we want to find the function. For example, we know velocity and want to calculate the space.

The process of finding a function from its derivative is called antidifferentiation, finding a primitive function, or finding an indefinite integral. As the name implies, antidifferentiation is an inverse operation to differentiation.

The use of the word integration here could seem odd because the problem of integration is related in some way with the finding of an area (accumulation, summation) and differentiation is related with the instantaneous rate of change or as the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function. We are going to see later then this two very different problems are deeply connected (Fundamental Theorem of Calculus) and that, in some way, integration is the inverse process of differentiation.

F(x) is said to be an antiderivative (or a primitive or an indefinite integral) of f(x) on an open interval if the derivative of F is f for every value of x on the interval.

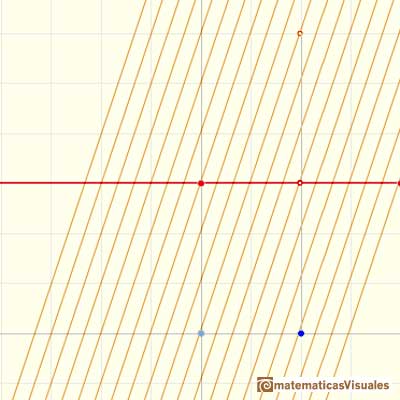

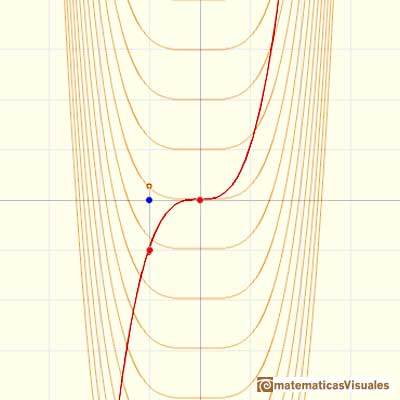

Notice that we define an antiderivative and not the antiderivative. This is because an antiderivative is not unique. Nevertheless the antiderivative is unique up to an additive constant. It is say:

Any two antiderivatives F and G of the same function f can differ only by a constant.

The reason is because their difference F-G has the derivative 0 and then F-G is a constant function.

Sometimes we use a particular sign (from Leibniz, the sign for integration is a large 's' from 'sum'. Leibniz used the following sign to denote a general primitive of f):

The function f is called the integrand, the constant C is called the constant of integration. The symbol dx indicates that we are to integrate with respect to x.

If we know simple techniques of differentiation to find some antiderivatives is easy. For example, it is straightforward to find a primitive for a constant function:

We can check that in each point the derivative is the original constant function:

The derivative of a polynomial of degree 1 (linear function) is a constant function (degree 0, an horizontal line). Then, an antiderivative of a constant function is a linear function.

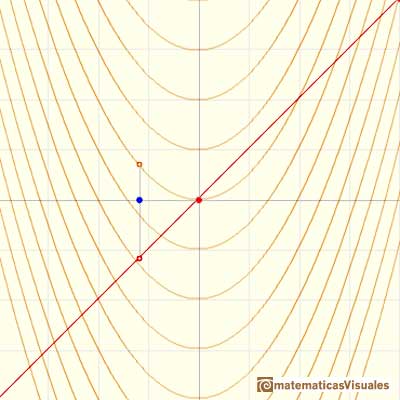

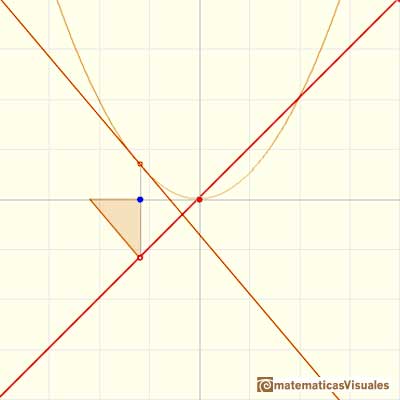

Antiderivatives of polynomials functions are easy too. For example, a basic linear function (the identity function):

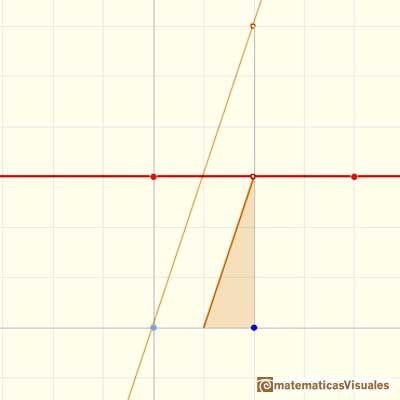

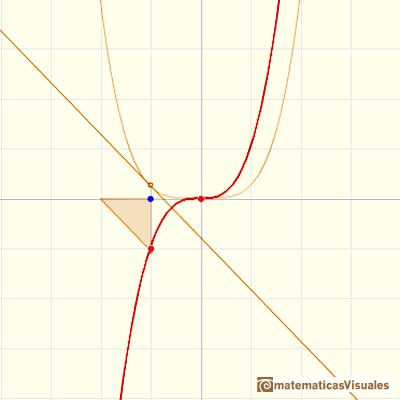

Checking the result in one point:

The derivative of a polynomial of degree 2 (a parabola) is a polynomial of degree 1 (a linear function). Then, a primitive of linear function is a parabola.

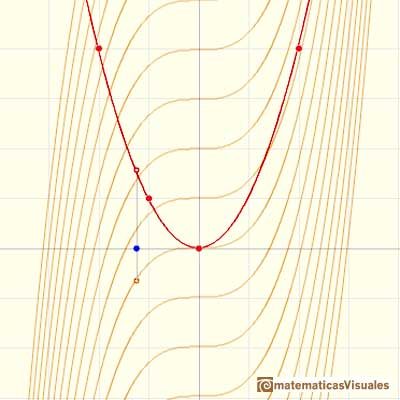

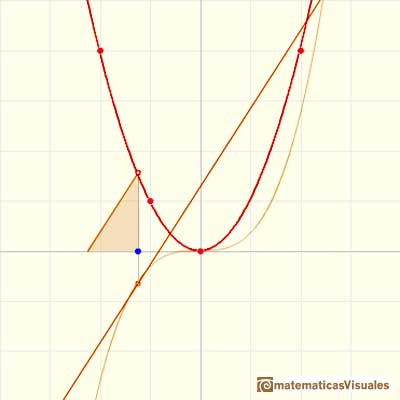

A quadratic polynomial (a parabola):

The derivative of a polynomial of degree 3 (a cubic) is a polynomial of degree 2 (a parabola). Then, an antiderivative of a parabola is a cubic function.

Another example, a cubic polynomial:

In the next version of the interactive application you can move the blue dot along the x-axis:

When we differentiate a polynomial function we get a polynomial function of one degree less than the original function. When we find an antiderivative of a polynomial function we get a polynomial function of one degree more than the original function.

Although finding primitives of polynomial functions is easy, to find an antiderivative turns out to be a difficult problem in general. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus tell us that we can always construct an antiderivative (primitive) of a continuous function by integration.

REFERENCES

NEXT

NEXT

PREVIOUS

PREVIOUS

MORE LINKS